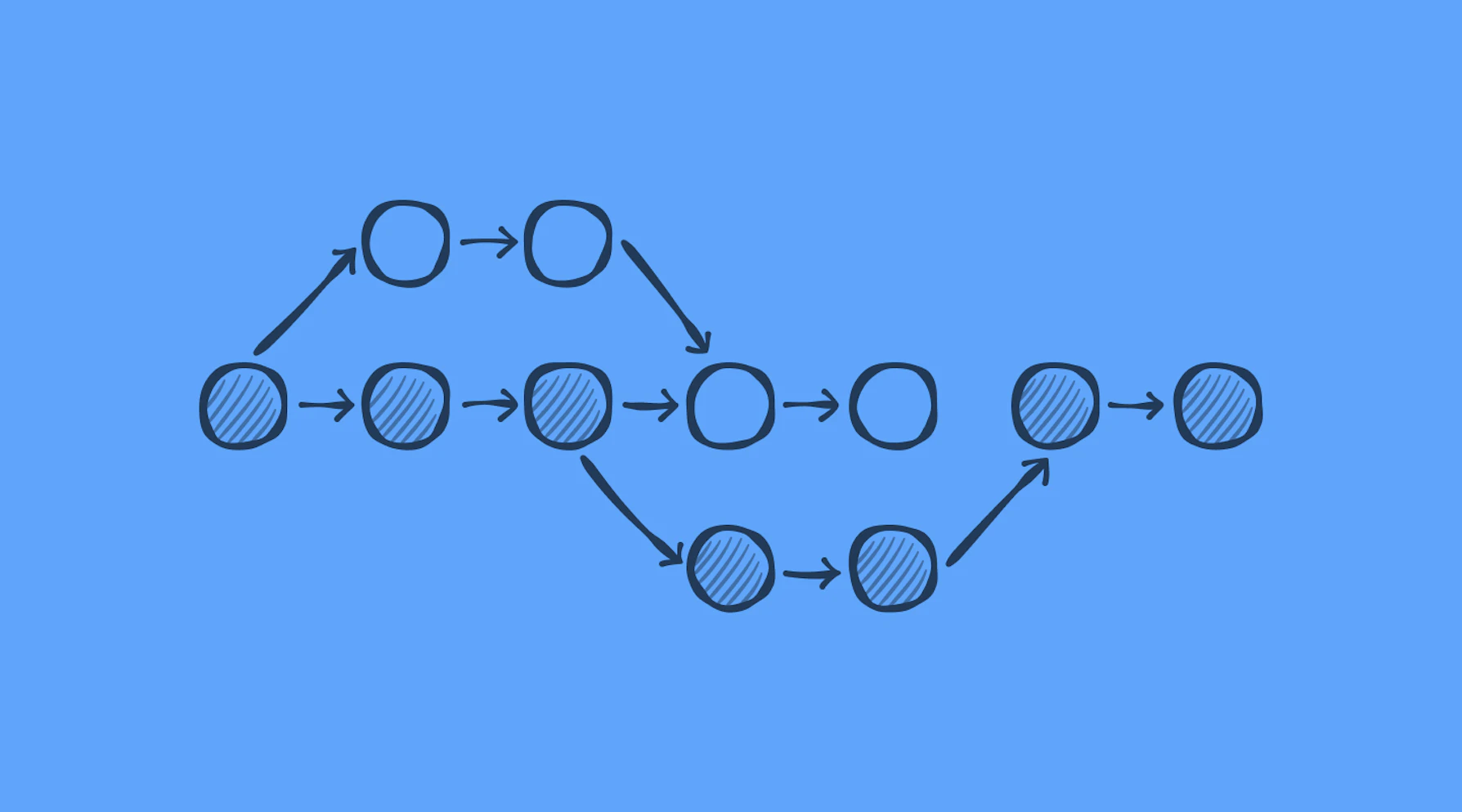

As a developer, you live and breathe branches. You create them for new features, bug fixes, and experiments. But at some point, that isolated work needs to be integrated back into the main line of development. In the world of Git, two powerful commands stand ready to help: git merge and git rebase.

Choosing between them is one of the most common points of debate and confusion among Git users. Both can achieve the goal of combining work from different branches, but they do so with fundamentally different philosophies and results. Understanding this difference is not just academic—it directly impacts your project's history, your team's workflow, and your ability to debug issues down the line.

This guide will provide a deep dive into both commands. We'll explore how they work under the hood, visualize their impact on your commit history, discuss how to handle conflicts, and introduce powerful related techniques like interactive rebase. By the end, you'll be able to confidently choose the right tool for the right job.

Part 1: git merge - The Story Preserver

git merge is the workhorse of branch integration. Its primary goal is to take the commits from a source branch and weave them into a target branch. The key takeaway for merge is that it preserves history as it happened.

How git merge Works

Let's imagine you're working on a new feature. You create a branch called feature/login from the main branch.

Initial State:

Your main branch has two commits.

A---B (main)

You create your feature branch from here.

A---B (main)

\

(feature/login)

Now, you add a commit to your feature branch.

A---B (main)

\

C (feature/login)

While you were working, a teammate pushed a new commit (D) to the main branch. The project history has now diverged.

D (main)

/

A---B

\

C (feature/login)

To integrate your feature, you switch to the target branch (main) and run the merge command:

# Switch to the branch you want to merge INTO

git switch main

# Merge the feature branch INTO main

git merge feature/login

Git performs a three-way merge. It looks at three commits to make its decision:

- The tip of the

mainbranch (D) - The tip of the

feature/loginbranch (C) - Their common ancestor (

B)

It then creates a brand new commit, called a merge commit. This special commit has two parents (C and D) and represents the reconciliation of these two divergent histories.

The Result:

The history now looks like this, with the new merge commit E.

D-------E (main)

/ /

A---B---------C (feature/login)

The "Fast-Forward" Merge

What if the main branch had not changed while you were working on your feature?

A---B (main)

\

C (feature/login)

In this case, when you run git merge feature/login, Git sees that main is a direct ancestor of feature/login. It doesn't need to create a merge commit. It simply "fast-forwards" the main pointer to point to the same commit as your feature branch.

A---B---C (main, feature/login)

This results in a perfectly linear history.

Handling Merge Conflicts

Conflicts happen when both branches have changed the same part of the same file. When you try to merge, Git will pause and tell you there's a conflict.

$ git merge feature/login

Auto-merging index.js

CONFLICT (content): Merge conflict in index.js

Automatic merge failed; fix conflicts and then commit the result.

To resolve it:

- Check the status:

git statuswill show you which files are in conflict. - Open the file: Inside the conflicted file, Git marks the problematic areas:

<<<<<<< HEAD

// Code from main branch

const greeting = 'Hello, World!';

=======

// Code from your feature branch

const greeting = 'Hi, Universe!';

>>>>>>> feature/login - Edit the file: Manually edit the code to be the final version you want. Remove the

<<<<<<<,=======, and>>>>>>>markers. - Stage the file:

git add <conflicted-file-name> - Commit: Run

git commit. Git will see you're in the middle of a merge and create the merge commit for you, completing the process.

Pros of git merge:

- Traceability: The history is a true and accurate log of what happened. A merge commit acts as a clear record that a feature was integrated.

- Non-destructive: It never changes existing commits, which is a safe practice, especially for shared branches.

- Contextual: It keeps the context of a feature branch intact—you can see the entire history of the branch's development.

Cons of git merge:

- Cluttered History: If your team merges frequently, the

git log --graphcan become a complex, branching mess of merge commits that is hard to read.

Part 2: git rebase - The History Rewriter

git rebase offers a different way to combine work. Instead of creating a merge commit, its goal is to create a clean, linear history. It achieves this by rewriting commits.

How git rebase Works

Let's use the same divergent history scenario:

D (main)

/

A---B

\

C (feature/login)

To use rebase, you check out the branch you want to move (feature/login) and rebase it onto the target (main).

# Switch to the branch with your work

git switch feature/login

# Rebase it onto the main branch

git rebase main

Git does the following:

- Finds the common ancestor (

B). - "Saves" the commits unique to your feature branch (in this case,

C) as temporary patches. - Resets your

feature/loginbranch to the latest commit onmain(D). - Applies the saved patches one by one, creating new commits on top of

main.

The Result:

The history becomes perfectly linear. Notice that C has become C', indicating it's a new commit with the same changes.

A---B---D---C' (feature/login)

\

(main)

The old commit C is now orphaned and will eventually be garbage collected by Git. Now, feature/login can be fast-forward merged into main.

git switch main

git merge feature/login # This will be a simple fast-forward

The Golden Rule of Rebasing

Because rebase rewrites history by creating new commits, there is one critical rule you must always follow:

Do not rebase a branch that is shared publicly with others.

If you rebase a branch that your teammates have pulled, you are creating a divergent history. Their repository still has the old commits, while yours has the new, rewritten ones. When you both try to push, Git will become hopelessly confused. Only rebase branches that exist locally on your machine.

Interactive Rebase: Your Personal History Janitor

One of the most powerful features of rebase is its interactive mode: git rebase -i. This allows you to clean up your own local commit history before you share your work with others.

Imagine you're on your feature branch and your history looks messy:

A---B---C---D---E (feature/login)

- Commit

C: "WIP" - Commit

D: "fixed a typo" - Commit

E: "actually implement the feature"

Before you merge this, you can clean it up.

# Rebase interactively against the commit you branched from (B's hash, or main)

git rebase -i main

This opens a text editor with a list of your commits:

pick <hash_C> WIP

pick <hash_D> fixed a typo

pick <hash_E> actually implement the feature

# Commands:

# p, pick = use commit

# s, squash = use commit, but meld into previous commit

# ... and others like reword, edit, drop

You can change pick to squash to combine the first two commits into the third one.

pick <hash_C> WIP

squash <hash_D> fixed a typo

squash <hash_E> actually implement the feature

Save and close. Git will then prompt you to write a new, clean commit message for the combined commit. Your history now looks pristine:

A---B---F (feature/login)

Where F is a single, clean commit titled "Implement User Login Feature".

Pros of git rebase:

- Linear History: The primary benefit is a clean, easy-to-read commit history.

- Clarity: It's easier to follow the progression of the project without noisy merge commits.

- Powerful Cleanup: Interactive rebase is an incredible tool for crafting a meaningful commit history.

Cons of git rebase:

- Rewrites History: This can be dangerous if not used correctly on private branches.

- Loses Context: You lose the record of when a branch was created and merged.

- More Complex: It can be more complex to handle conflicts, as you may have to resolve them on each commit being replayed.

Head-to-Head: Merge vs. Rebase

| Feature | git merge | git rebase |

|---|---|---|

| History Shape | Branching, graph-like (non-linear) | Perfectly linear |

| History Integrity | Preserves original commits; adds a merge commit | Rewrites commits, creating new ones |

| Collaboration | Safe for public, shared branches | Safe only for local, private branches |

| Ease of Use | Simpler concept, fewer risks | More complex, requires understanding the "Golden Rule" |

| Conflict Resolution | Resolve all conflicts at once, then commit | Resolve conflicts one commit at a time as they are replayed |

Conclusion: Which One Should You Use?

There is no single "better" command. The choice depends entirely on your team's workflow and preferences.

Choose

git mergewhen:- You are working on a shared/public branch.

- Your team values a precise and untampered historical record.

- You want to maintain the distinct context of a feature branch.

Choose

git rebasewhen:- You are working on your own local, private branch.

- You want to present a clean, linear series of commits to the main branch.

- You value a readable project history over a strictly chronological one.

A popular and effective workflow is to use rebase locally to clean up your own work and then merge it into the shared branch. This gives you the best of both worlds: a clean feature history combined with a merge commit that signals the integration of a complete feature.

The best way to learn is to try. Create a test repository, make some branches, and see for yourself how merge and rebase shape the history. Gaining mastery over these two commands will make you a more effective and collaborative developer.